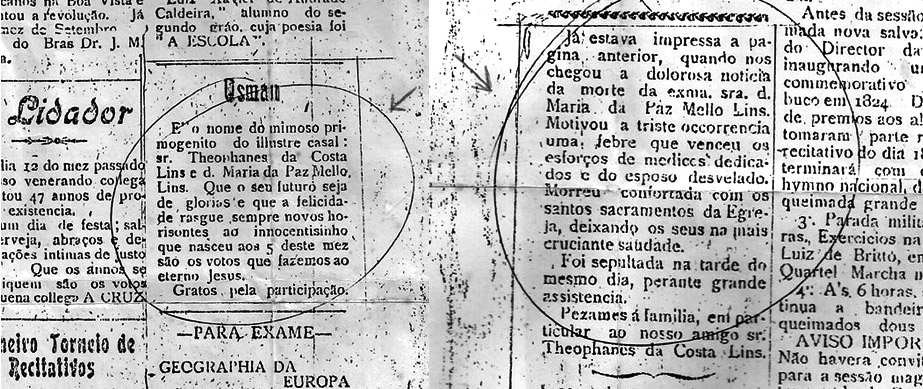

It was the month of July 1924. In the small town of Vitória de Santo Antão, in the Pernambuco countryside, where everybody knew one another, the monthly edition of the A Cruz newspaper caused a stir. Readers had already heard the news. But seeing it so starkly put in print made it all the more poignant. Page 3 reported the birth of Osman Lins and the back page the death of his mother of postpartum complications, sixteen days later.

A wet nurse called Rosa was promptly hired by the family to feed the newborn baby. Osman always showed deep affection and regularly visited “Mama Rosa”, as he called her, and he dedicated The Visitor, his first book, “To my Rosa” and also named a character in the novel after her. Maria da Paz, dead at 18, left around two hundred written poems that were destroyed shortly after her death by her distraught widower who could not bear the memories they evoked. Were these merely the reveries of a dreamy adolescent or poems of great literary value? Unfortunately we will never know.

Joana Carolina, the writer’s paternal grandmother (who had been widowed in 1902, at the age of 28 with four children), did the best she could to console her son Teóphanes and took over the raising and education of her grandchild, along with her daughter Laura and her son-in-law, Antonio Figueiredo. The latter was a great story teller and instilled a love of narration in his nephew. Through Joana Carolina, a retired schoolteacher, the boy became acquainted with the world of reading and writing. When he started to attend Vitória High School the following decade, young Osman already knew how to read and write without help. The trained eye of his teacher, José Aragão, recognized his aptitude for self-expression and his passion for words. He encouraged him to write and advised him on suitable reading matter.

At the age of eight, he wrote his first poem, “Bedouin Regenerated by the Moon”. It was criticized for lacking meter and rhyme, but the boy was undiscouraged. He carried on writing.

Many years later, as an adult, when asked in an interview about the difficulties confronting a writer, he replied, “I confront them stubbornly. With clenched fists and gritted teeth, I hurl myself at them. One way or another, whether they like it or not, I will leave my mark.” Any kind of repression troubled him greatly, and the military dictatorship, by which he was affected personally, intensified his struggle for human rights, freedom of expression and social justice, giving his writings in periodicals and his fiction a more vivid tone. He doggedly fought to improve the lamentable state of the country. He turned down invitations to literary events promoted by the government, because he did not want to relinquish his freedom to protest. Fully independent, he never accepted any outside support in promoting his work, even overseas. He relied on his own talents and resources alone. He was the first Brazilian author included on the site of the Paris Conseil International des Archives.

At 17, when he moved from Vitória de Santo Antão to Recife, Osman already had his first short stories in his knapsack and these were soon published in local newspapers. The first two, posted here, were entitled “Bad Boy” and “Ghosts…”. Later, not necessarily in chronological order, we will post the other short stories, articles, poems, and literary essays that he published in a range of media outlets between 1941 and 1978.

As a teenager, already firmly committed to becoming a writer, Osman Lins applied for a position at Banco do Brasil. As he worked only in the afternoon, his mornings were free and the bank also provided him sufficient economic security to be able dedicate himself to his true vocation, the art of writing. As he was still a minor, his father had to accompany him when he first took up the job at the bank.

At 20 years of age, he enrolled in a drama course and continued to publish essays, stories, criticism, and poetry in the literary supplements of local newspapers. He also produced and directed arts programs for Recife local radio.

He wrote daily pieces for the “Alô, amigos!” radio show and adapted the work of Shakespeare, Machado de Assis, and Katherine Mansfield, among others.

In 1946, he concluded an Accounting Course at Recife’s Faculty of Economic Sciences and married Maria do Carmo de Amorim Araújo, with whom he had three daughters. He continued to write extensively, accumulating prizes for works such as his short story collections The Donation, The Echo and The Alone. His play The Sunless Valley was awarded special recognition by the 1957 Tônia-Celi-Autran Company competition. He published poems such as Instant, Tramway Lamentation, The Corolla, The Image, Naive Little Sonnet, Poem on the Best Way to Love, Recife Serenade for Cacilda Becker, Offering Sonnet, and Architectonic Sonnet, and he started writing the column Letter from Recife, later renamed Recife Chronicle. By this time, Osman Lins had already written two novels, Deep Night and The Mirrors, which he never published because he considered them merely exercises undertaken as a preparation for greater things to come.

While still living in Recife, he also contributed to the O Estado de São Paulo, in which, in 1958, he published his first non-conformist and polemical articles. Meanwhile he was still writing short stories and accumulating prizes at local and national level. In 1955, he launched his first novel, The Visitor.

Osman was a perfectionist who meticulously researched and planned everything he wrote. By way of illustration, when he was working on War without Witness, he simultaneously wrote the book itself and a diary accompanying its production.

In 1961, at the age of 36, he spent six months in France, on an Alliance Française scholarship, which afforded him first-hand knowledge of the noveau roman. A fluent speaker of French, he also worked as theater critic for Jornal do Commercio during his six-month stay. While he was away, his play Lisbela and the Prisoner was staged for the first time and received the Tônia-Celi-Autran Company Prize. He also launched his novel The Faithful and the Stone, which received an award from the Brazilian Writers Union – Recife. His experience of living in Europe gave rise to Maiden Voyage Sailor and, in 1971, he started to publish his work abroad.

Back from France, he moved with his wife and daughters to São Paulo, got divorced and married Julieta de Godoy Ladeira.

In 1970, alongside his writing career, Osman became professor of Brazilian Literature at the Marília Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, São Paulo, and, in 1973, he was awarded the title of Doctor of Letters from the same institution, for the thesis “Romanesque Space in Lima Barreto”, which led him to write, relieved, to his great friend Lauro de Oliveira, on 11 December 1973, “…I am dedicating this morning to updating my correspondence… Yesterday, the 10th, I defended my doctoral thesis at Marília and was unanimously awarded a distinction. The viva lasted almost five hours and the examiners, apart from Alfredo Bosi, my supervisor, included Antonio Cândido, João Alexandre Barbosa, Nelly Novaes Coelho and a linguistics professor called Maria Teresa Biderman. Your friend is now a Doctor of Letters and no longer a Bachelor of Economic Sciences, which was a total nonsense that bothered me. I am now a citizen of the world of letters, so to speak…”

His classes were very enriching and he recorded them, but, after three years, he left the faculty feeling disillusioned and powerless. It is hard to find someone who dedicated themselves as diligently as Osman Lins to their profession. He was always questioning himself as a writer and his role in the world; and wondering whether he was giving his best to his readers. He recognized what is called “the profound significance of the act of writing” and he knew what he called “the joy of the written word”. “I would not swap this for anything. Everything I know of life, my relationships, my deepest and most enriching friendships, all of this came through literature. We reach out to those who are our brothers and sisters in the world. We operate in a world that as a whole is hostile or indifferent to our work. But how can one describe the joy of finding an attentive reader when we are least expecting it? It is something so powerful that it overcomes the barriers of translation. I have received reactions, even from foreign readers, that border on tenderness. Can you imagine what this means? One human being reaching out to the heart of another human being, overcoming all barriers, including those of a linguistic nature. Who other than an artist knows this joy?”

In a hostile and indifferent world where the values in which he believed and for which he lived were mostly neglected, Osman Lins blazed a trail to be followed by all those who wish to follow a path that is perhaps less easy, but more worthy and honorable: a path capable of leading to less somber places, or places where the shadows can be transformed into light for some, or perhaps for many.

Osman Lins fell asleep on the morning of 8 July 1978 and never woke up. He had lost his last battle, against cancer.